Scott Miller, 1960-2013

(I have started and stopped this post over a dozen times in the last week. Writing it has left me in tears more often than I care to admit. There are many things I want to say about Scott Miller’s art–his music–but right now does not feel like an appropriate time to say them. Instead, I would like to give a final homage to Scott Miller, the man.)

“Our Scott”

Years ago my friend Mike speculated on how odd it must be to be Scott Miller. Imagine that you’re Scott, a normal guy doing normal guy stuff. You’ve got a job, family, a home, and you do stuff that guys with jobs, families, and homes do 99.99% of the time. But…there’s always that one time for you where you’re having a coffee, or waiting in line at the DMV or eating dinner in a restaurant when someone recognizes you and that someone swarms over you with the kind of adulation normally reserved for people who are a lot less unassuming than Scott Miller was.

That would be the crazy part of being him: the recognition. Because the thing is, people who would recognize Scott Miller don’t just “recognize” the guy. No, if you’re able to pick him out of a lineup, you’re likely a fan, and if you’re a fan of Scott Miller’s music, there’s not a whole lot of middle ground there. As such, Mike wondered about the awkwardness of Scott standing at a urinal stall or browsing in the cereal aisle at the grocery and suddenly getting accosted by one of us over-eager fans desperate to tell an idol how awesome he was.

Don’t laugh. That’s the kind of personal relationship Scott seems to have inspired in so many of his fans. Something about his music seems to speak personally to those of us who get hooked by it. The joys and pains and happinesses and hurts of life are usually far more multifaceted than we’re easily able to express; Scott Miller’s genius was to embrace the complexity in those emotions and expound upon them eloquently, perhaps too much so to ever capture a mass audience…but for those willing to combine a nerd-ish frame of cultural obsession with a need for introspection, Miller hit like a ton of bricks.

You See The World Just As I Do

My own Scott Miller testimony goes like this. From my senior year in high school into my freshman year in college I’d begun to articulate past the classic rock of my early days to see how folks like REM or the Replacements sort of could trace a connection back to artists and records I was more familiar with. Through the Replacements and an interview in Creem or something, I learned of the existence of Big Star, and paid too much money for a double-length cassette (The People’s Format plays a starring role in this tale of mid-80’s self-discovery) of those first two Big Star albums shortly thereafter. About the same time I’d picked up a copy of Ira Robbins’ Trouser Press Record Guide (1985 version), and somehow decided that based on glowing reviews from the book, I really would like the music of Agent Orange and Plan 9, if only given the actual opportunity of hearing said music. (Yes kids, before the internet you’d buy music based upon critical description of it in words, rather than actually hearing it.) One aimless afternoon at the MusicVision store in Cave Springs, Missouri in that summer of 1987, I found a cassette called The Enigma Variations 2–basically a label comp for Enigma Records bands. Jackpot. It had not only two songs each from Agent Orange and Plan 9, but also one from Mojo & Skid.

Please don’t laugh. It was 1987.

Somewhere on that tape–probably after the lame SSQ song–this revelatory thing happened. It was called “Erica’s Word” by a band called Game Theory, writing credit to one S. Miller, the band’s frontman. I think I rewound the tape and played it over and over again, and then seeing a song called “Shark Pretty” by the same band on the other side of the tape, I listened to that over as well. Later that same day I was back at MusicVision buying Big Shot Chronicles. I was hooked completely, immediately grabbing onto the connection with and influence of Alex Chilton and Big Star. It likely helped that this same summer the girl I had been dating for 2 years brought the sky down on my head and caused me my first real relationship heartbreak. To say I was ready for the sentiment of “Erica’s Word” or “Make Any Vows” or “Too Closely” at that moment was an understatement.

When I got back to Mizzou in early August of that year (some buddies and I had taken off-campus housing), I happened to hear “Waltz The Halls Always” on KCOU, the campus station I didn’t yet work for but soon would. This was revelatory. I hadn’t yet been able to track down the EP with “Shark Pretty” on it, so I’d assumed it was very rare (it was in the midwest) and guessed that all Game Theory stuff to be similarly hard to come by. “Waltz” was a totally new song to me, and it amazed me, and thus later that day I was delighted to discover Real Nighttime at Streetside Records on Broadway. Still remember that Robb Moore rang up the sale and said “This is a great record,” and made sure that I already had BSC.

(A brief interlude: I cannot believe I have thus far failed to mention that for the time being, every Game Theory album can be snagged and downloaded for free here: http://www.loudfamily.com/ If you don’t have them, you need them. Start with “Erica’s Word” like I did.)

That fall before Lolita Nation came out, I wrote a fan letter–something I absolutely never had done before or since. In fact, I didn’t think of it as a fan letter. Although there was a fan club address on the cover of Big Shot Chronicles that I had to address the letter to, I think I had the pretension to say something snotty to the effect of “Hey, this is for Scott, really don’t much do the fan club thing, thanks.” Basically, I wrote Scott and told him I was a big fan, told him how much his music meant to me, how much it helped me get through blah blah blah. Typical stuff, I’m sure. I was stunned a few weeks later when Scott wrote back, and wrote a longer letter than I’d sent. He thanked me profusely for taking the time to write, mentioned that he hoped they’d get to Columbia on their next tour (they’d missed my college town on their most recent). I’d mentioned I had family in the San Francisco area in my letter. Scott’s letter ended with him saying that if I had free time on a visit to give him a call to maybe hang out.

Seriously. It said that. Still have it.

Perhaps that doesn’t make an impact, so let me try to couch it in ways that can help makes sense for how that hit me: imagine writing to Leonardo Da Vinci to tell him how much you admire his art, and Leo messages you back with “Thanks! We should have a beer together sometime if you’re ever in Milan.”

When Game Theory did get to Columbia for their final major tour after the release of 2 Steps From The Middle Ages, I was stunned when Scott seemed to almost recognize me before I introduced myself. I wouldn’t see him again until 1993 on the first Loud Family tour. That time he walked right up to me in the basement at Cicero’s and said “Hi…Chris, right?” That’s how things continued. Saw the Loud Family play two shows in St. Louis, saw them twice in Chicago after I moved there, had a water or coffee or beer with Scott at a few of those shows and just sort of chatted about whatever.

A Nice Guy As Minor Celebrities Go

I tell all that not to paint myself as an insider or blow my own horn. Hardly could be any less true. The reason I tell that story is because there are perhaps 200-300 folks across the country who Scott Miller treated the same way. People who this unbelievably talented artist made to feel like a friend, made to feel important in our own ways. 200-300 people who likely have pretty much the exact same Scott Miller story of their own to tell. I’ve heard stories of fans who were 18 and not allowed into a club where Game Theory was playing, and Scott resourcefully having that person carry a guitar into the club and informing the staff there in all seriousness that said teenager was an essential member of the band’s road crew, thus allowing that person to stay for the show. One memorable story I read was from a fan who informed Miller after a Game Theory show that she was bummed the band didn’t do “Together Now Very Minor”. Scott put that person on a guest list for the next show up the road, and told her to get there for soundcheck if possible. When she arrived the rest of the band had already split to grab a pre-show meal and she found Scott the only person still hanging around the club. Miller dutifully pulled out a guitar and played “Together Now” solo in an empty club for one person’s enjoyment.

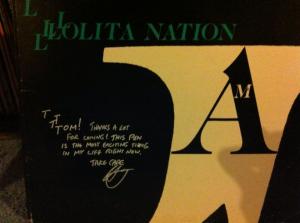

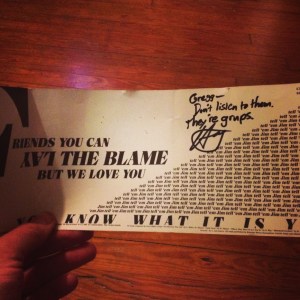

Scott Miller also never just signed his name on an autograph. His signatures always conveyed a sense of whimsy and artful amusement, like so (clicking the images embiggens; I am reliably informed that the bottom image is exceedingly funny for folks who know their Star Trek):

She’ll Be A Verb When You’re A Noun

Although reading interviews with Miller over the years reveals a thoughtful, humble and deep thinker, none of that prepared me for the brilliance of Scott Miller’s music criticism. Published as a book a few years ago, Music: What Happened? is almost absurdly good. The premise is simple: Miller had kept notebooks listing his favorite songs of every year in order, chronologically from 1957. The book allowed him to present songs from those lists as a sort of written-down mix-tape, with amazingly spot-on, funny, and sometimes moving commentary about each song and artist. One of my favorite pieces touches on a completely counter-intuitive premise, but one the author defends brilliantly:

“The nineties were better than the eighties, and one key reason was that there was less originality. Originality is unmusical. The urge to do music is an admiring emulation of music one loves; the urge toward orginality happens under threat that the music that sounds good to you somehow isn’t good enough. In the nineties, bands pretty much all had a single thought: we want to be the next Nirvana. Bands had the least fear in years that following their hearts and doing straight fuzz-guitar pop-rock was somehow old-fashioned. There were a lot of good songs. Life was simple.”

The book is full of similarly smart, thoughtful, and well-argued points that will make you go diving into your record collection to hear songs you know by heart in new ways. Perhaps even better, it sends you down paths of exploration into new music happily and willingly. That’s a tough trick to turn for a music writer.

DEFMACROS / HOWSOMETH /INGDOTIME /

In the most recent post to this you can find the link to donate to the education fund for Scott Miller’s two daughters. Perhaps most heartbreaking things for me to read over the last week were comments there from folks who likely had no idea that they were working alongside a beloved musician–Scott’s co-workers at the tech company where he was an engineer. They perhaps didn’t know Miller as the guy who wrote the soundtrack of the uncomfortable post-collegiate years of so many others. No, they knew Scott as the warm and funny and interesting and helpful co-worker. It always rather boggled my mind that a guy who wrote such agile, gorgeous melodies and who clearly had such mastery of pop culture and literature had earned an engineering degree from UC-Davis. I know engineers. As a matter of fact, I know plenty of them. Engineers just…well, they sure don’t know (or care) who Eliot or Joyce were, that’s dead certain. At least not usually.

Always The Eyes, Never The View

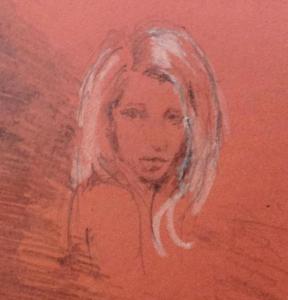

It is also worth noting that Scott Miller was very much into visual artistry. Looking back at Game Theory covers and then on into the Loud Family, Miller’s infatuation with elements of graphic design and typography are obvious and on display. What I never realized was the gift he had for drawing. Scott’s lovely wife Kristine (who has frankly been a marvel in the last week, managing to somehow through her own grief share remembrances and nuances of Miller with fans) posted these sketches of her and the family that Scott had done fairly recently:

These were sketched from original family portraits. As Mrs. Miller tells it, Scott would likely dismiss any compliments on the work because he’d just been drawing from photographs, but even so…the likenesses are stunning and accurate and perhaps capture even more than the photos they’re based on can convey. So yeah. Dude could draw too. Kind of amazing.

Go Ahead And Scare Me With The End

I realize that at this point I’m mostly rambling about the death of a guy I knew only in passing. I guess what I really wanted to convey is maybe a fraction of why those of us who are so sad and grief-stricken and bewildered right now feel that way. The world is a messed up, arbitrary, frequently angry and ugly place. It needs people in it like Scott Miller to shine the light on the beautiful and worth-living parts of it. One of those lights has dimmed now, and that’s why I am so sad. Scott Miller was one of the most unique and interesting and charming and humble and talented and beautiful human beings I have ever had the pleasure to have known, and I will miss the light he brought into the world terribly.

______________________________________________________

Not Yet.

I was very close to posting some remarks of my own regarding the sudden passing of Scott Miller a week ago today. Thankfully, I saw this first and realized the time is not quite right for me to have my say:

http://www.gofundme.com/2nz0vk

I cannot look at the pictures of Scott and Kristine and their lovely family and not feel overcome with grief all over again. Much love to those so close to him who have to go forward with living life. If you have the means to give a little, it’ll be appreciated.

Permalink Comments Off on Not Yet.

The Notices I Never Thought Would Be Sent Out Have Arrived

On Monday, April 15th, Scott Miller died. I’m not sure the death of someone I only knew casually has ever devastated me this much. I am grief-stricken, and know that my own grief and pain is nothing like that which must be hitting his wife Kristine, their two daughters, and the many people who were lucky enough to be close friends with them.

I plan to write something…better…than this in a bit. I’m still trying to figure out how to say things about him coherently.

I find it odd how the human mind attempts to “bargain” when hit with astonishingly bad news. Last night when I heard of Scott’s passing, I went to the room where I keep my records and CD’s. There are thousands of pieces of music there. My computer has three terabytes of digital music stored on various auxiliary drives. I’ve got a lot of music, in other words, and music means a lot to me. With that said, in my mind the weird bargaining last night began with wondering if I’d willingly trade all that music just for the chance of Scott Miller still being alive and ready to record a new Game Theory album, as was the case?

Yes.

Would I be willing to give up all that music and never hear any of it again just for the chance of Scott Miller being alive and with his family and occasionally writing pithy and interesting and funny things about music again?

Yes.

Would I give it all up just to know that the guy who wrote and performed more music that carried me through more seas–both rough and calm–in my life was still around, even if I never heard another song from him or read another word he’d write?

Yes, I think. Yes to all that.

When my mother passed away last month after a very long and cruel illness (her passing was a blessing that relieved her suffering), I thought about posting a clip of her favorite song. I remember vividly in the time immediately after my father had died when I was a child, how music made it a little more okay, how it made me able to deal with things. Mom–who always sang all the time, much to my childhood chagrin–was constantly singing “Somewhere” from West Side Story. She confided in me once, years later, that she and my Dad thought of it as one of “their” songs, and it was her favorite. Oddly enough in his book Music–What Happened, Scott Miller called “Somewhere” his best song of 1957.

Two years ago Scott did a performance thing where he’d read bits from the book and then perform songs live that he’d praised in it. That night he did “Somewhere”, straining his voice to get the highest notes in proper Millerian fashion. I’d like to think that maybe in happier times, Scott sang that song around his own daughters. I hope that it will one day soothe them as it does me, and they’ll be thankful that they can hear their dad sing it still.

O Captain, My Captain.

1960-2013

“And please don’t pay attention to

A thing I do or say

It’s a ploy to drag you out

And take it all away

All away”

Learning To Think Critically.

It was early spring, 1993, I think. I’d roadtripped from St. Louis to my recent college haunts of Columbia, MO on a Friday to see Superchunk play a show at the Blue Note and had wisely–given the intake of beer at the show and then at the after-party that followed–decided to sleep it off on my old roommate Dan’s couch (which I was assured was the most comfortable couch imaginable).

I woke up, bleary-eyed and hung-over around 9 am the next morning, a Saturday. While 9 am now seems impossibly late in the day to be waking, at that moment in life it was just as impossibly early. I knew well no one else was going to be awake for hours, at least…and I had no idea where my car keys were to start back home. Rather than make a nuisance of myself and wake up the friends who were nice enough to give me a place to crash, I instead got up and had some water and settled back on the couch. I’d noticed a dog-eared copy of Roger Ebert’s Movie Guide for 1991 or 1992 on a cluttered coffee table, and I’m guessing it was Dan’s. Lacking anything better to read, I’d thumb through that.

At this stage in my life, all I knew of Roger Ebert was what I saw on television. He hated movies that teenaged me in high school liked, like Conan The Barbarian or Police Academy. If I thought of Ebert, I thought of him as a cranky movie snob, an overweaning, condescending and judgmental grouch who hated, well, everything.

The first review I paged to in that movie guide was one I was sure Ebert would savage: Animal House. I was fairly stunned to see him give it four stars and proclaim loudly its comic glories. I had no idea. I loved Animal House, but fully expected it to be the kind of low-brow humor that Roger Ebert hated, and hated very much. That he loved the movie– and loved it for exactly the same reasons I did–was a revelation.

I spent a few hours that morning reading reviews and realizing I had pegged Roger Ebert all wrong from the get-go. Everyone has a favorite Roger Ebert review, but I think the one that turned me into a raving fan that day was for the film The Reanimator.

No, that’s not a typo.

If you’re familiar with that film, a blood-spattered, sexploitation gorefest very loosely based on a short story by H. P. Lovecraft, you know that it is, to coin a phrase, a bit over the top. I’d convinced my girlfriend at the time to come see it with me (oops) at the theater when it was in release, based on the idea that it was Lovecraft, and Lovecraft was cool and scary. She wanted to leave, I think, halfway through. I sort of did too, but I was transfixed by the absurd trainwreck happening on-screen. If you’ve seen the movie, you know what I’m talking about. Each scene feels like an attempt to out-crazy the next, culminating with an extended sequence (and I’m not making this up) in which a bloody, headless reanimated body holds the decapitated-but-alive head of a mad scientist over the extremely naked, dead body of a woman while said disembodied head performs oral congress upon the nude body in rather graphic (for 1989), close-up fashion.

I expected Roger to absolutely hate The Reanimator. It was a sexist, violent, gory, overcooked ode to excess. And yet here in this movie guide, Ebert’s giving this crazy movie I expected him to hate three out of four stars. Crazier still, he’s actually praising the film for its excesses. To paraphrase the tone of the review, Roger admired the crazy genius of the director for being willing to totally go for it. In Ebert’s mind, if you’re going to make a gore-fest that suggests such absurdities as this film did, better to go for it completely and stomp on the accelerator and leave the half-measures for fainter hearts. While he knew the movie was utter garbage, he found it enjoyable garbage, precisely because the filmmakers held to the courage of their convictions to excess and went all out.

When I got home that weekend, I headed out to the bookstore (remember those) and picked up the newest version of Ebert’s Movie Companion. I loved the reviews. Surprising to me, I also loved the essays. I remember in particular an essay he’d written in the wake of Ted Turner committing heresy at the time by colorizing black and white movies. The essay was an ode to black and white films that explained why they were great in such detail and with such convincing and well-designed arguments that I was utterly sold. To this day I have an abiding love of black and white films of the classic days of cinema.

What I really learned, though, through that reading was two things. The first was easy to grasp: Roger Ebert was a tremendous writer, and put sentences together in ways that other critics and essayists could mostly only dream of. The second was a little more philosophical and took time for me to sort out. What I discovered was that I had completely mis-judged Ebert. He was no movie snob. He was no condescending grouch. Rather, he was the perfect moviegoing Everyman. Roger saw hundreds of movies a year–perhaps thousands in some years. What came through in 99% of his written reviews was that when the lights went down and the curtain lifted no matter what movie Ebert was seeing, whether it be The Godfather or Infra-Man, Roger wanted to like that movie very much.

I think that’s the key to Ebert’s legacy, and why he was such a great critic, and why he is so mourned today. You can count on the fingers of one hand (okay, perhaps two) the number of films in his career that Ebert went to see that he hated before seeing a single frame. Think about that for a moment. Frame it with music criticism if you like. If someone handed you a Nickleback CD and told you to review it, you’d be cringing at the expected awfulness you were about to hear. Roger Ebert did the movie equivalent of having to listen to a lot of Nickleback in his career. What’s impressive is that he found so many such films–movies that might be overlooked for lack of impact–to the praises of. Remember a movie called Joe Vs. The Volcano? Likely you don’t (if you do, it’s because of Tom Hanks). Roger Ebert gave it four stars and insisted through all time that it was one of the greatest films of 1990. To be certain, Ebert recognized genius in film in all the right places; what set him apart was recognizing it in places that everyone else had overlooked. That’s why you get a Roger Ebert commentary track on Citizen Kane…but also on Alex Proyas’s dystopian sci-fi noir film Dark City.

I tried to learn that from Roger Ebert. His movie reviews re-jiggered my own critical thought process on something I love as much as he loved movies–music. I learned that obscure doesn’t mean “great” any more than “popular” means “dreck”. I learned to see art as it happens (box of snickers to you if you know the reference of “Art as it happens”, btw. Seriously, impress me.) In this growth, Roger Ebert planted a seed and nurtured me well through the years with his movie reviews, but he was hardly alone.

At the same time in my life I began working at Euclid Records down in the Central West End in St. Louis. Again, I expected to find snobbishness as the rule of the day (only this time regarding music). Kudos then to a guy like Steve Scariano who’d play something like the Time-Life “Greatest Rock Hits Of 1969” collection on CD in-store without the slightest hint of irony. Kudos to Joe Schwab and Tom Boyle and Guy Burwell for playing Oasis and Radiohead and Blur and Soundgarden in the store and cracking my meat hard if I tried to diss any of them for being “too popular”, whatever the hell that meant. Thanks to that tutelage, I learned that great rock and roll records are great rock and roll records, whether they sell 10 copies or 10 million. I learned that ignoring something for being popular was a good way to exclude myself from hearing and appreciating great music.

The appreciation of the mainstream and popular as having the possibility of sitting on equal artistic ground as the obscure is a lesson I still try to carry forward. David Byron (who in addition to being the smartest person I know) is, in some lives, a collegiate art historian who simply knows more about art than I’ll ever know about anything. When I come back from an afternoon at the National Gallery here in DC, he doesn’t tell me I’m a philistine with infantile taste for asking about some of the paintings I ply him about. Rather, he enthusiastically tells me why paintings that I’ve predisposed to believe are simplistic and pedestrian (mostly due to the fact that they caught my horribly untrained eye and interested me) are anything but, and explains why those paintings drew my eyes and caused me to remark upon them. Are there more obscure, interesting, and worthwhile paintings in the gallery than the ones I might be asking about? Of course…but again, I learn from David how the popular (and perhaps even mundane) can, with the proper perspective rise far above being mere crowd-pleasers.

I’ve come to think of this celebration of finding nuggets of great beauty and art and worthwhileness in the most unlikely areas of extremely popular art as “The Fifty Million Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong” Postulation. I swear by it and try to uphold it as the backbone of every bit of critical thinking I engage in as an adult. No one critic in any medium I know of embraced that more fully than Roger Ebert. That he is gone now is sad, but that he lived and wrote and wrote so much and so well is a happy thing indeed.

Thank you, Roger Ebert. Thank you for teaching me to love black and white movies. Thank you for writing things that made me want to see movies like Days Of Heaven and Cries And Whispers. Thank you for making the case that Joe Vs. The Volcano and Dark City were every bit as worthwhile as those other two films. Thank you for teaching me about fruit carts and the proper way to enjoy a popcorn movie. Thank you for teaching me to think and draw conclusions…and then be willing to scrub those conclusions off the board at some later date in life and arrive at new conclusions from the same material.

I shall, in my own tiny way, attempt to pay those lessons forward with everything I write. Rest in peace.